Unlocking Wealth: Trump’s Strategy in the Mineral-Rich Conflict of DR Congo

In a bold move to transform Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), the Trump administration is driving a controversial peace initiative aimed at resolving decades-long conflicts fueled by rich mineral resources. The US, which is heavily reliant on the minerals found in DR Congo to support its technological advancements, is looking to secure these resources as part of a diplomatic deal with Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi and Rwandan President Paul Kagame. With plans to host the leaders for a ceremonial peace agreement, Trump heralds this effort as a potential ”glorious triumph”.

Experts highlight that DR Congo has $25 trillion in mineral reserves – including cobalt, copper, lithium, and tantalum – essential for the tech and military industries. However, there’s skepticism regarding the US’s ability to catch up with China, which has already secured many mineral extraction rights in the region. Prof. Alex de Waal, from the World Peace Foundation, believes that Trump’s approach is innovative, merging political gain with economic interests, yet warns of potential pitfalls regarding DR Congo’s sovereignty over its mineral wealth.

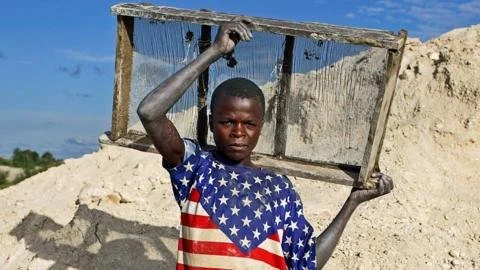

Crucially, security concerns have previously deterred US investments, as companies are wary of engaging in regions afflicted by violence and conflict over what are referred to as ”blood minerals”. Despite hesitation, this new peace model could lead to significant changes if it successfully curtails violence that has killed thousands and displaced millions.

Moreover, while the US aims for stronger ties and economic partnerships, there are potential compromises regarding long-term agreements for mineral rights that could bind DR Congo under unfavorable terms. Prof. Hanri Mostert’s insights suggest that such arrangements might be reminiscent of previous patterns where African nations have sacrificed their sovereignty for immediate security and infrastructure needs, a concern that echoes historical exploitation of resources.

With peace discussions underway, the involvement of external players like Qatar, which focuses on domestic issues between DR Congo and the M23 rebel group, complicates the dynamics of the negotiation process. Experts caution that the success of a peace agreement hinges not just on diplomatic negotiations, but on addressing historical grievances and ensuring genuine local participation to transform long-standing injustices.

The road ahead for transforming DR Congo through this US-led initiative remains uncertain. Trump may need to sustain pressure and engage with multiple stakeholders to ensure that the peace deal holds long enough for US businesses to reap potential profits, even as the M23 and other rebel groups pose significant challenges to stability. As tensions ebb and flow, observers remain keenly aware that true peace requires far more than mere agreements; it necessitates addressing the pain and trauma rooted deeply within Congolese society.